Author: Ion Drew, University of Stavanger

Topic/Subject area: Methodological approaches

What is Readers' Theatre?

Readers Theatre is a group reading activity. In some forms it also involves dramatisation. Its origins go back thousands of years to the oral tradition of story-telling in ancient Greece. In the 1950s and 1960s it was a recognised form of theatre in the USA and England with, for example, productions on Broadway and by the Royal Shakespeare Company. It later spread to colleges and schools, where it was considered to have an enormous potential both in mother tongue and foreign language classrooms.

The basic principle of Readers Theatre is that a text is read aloud in small pieces at a time by a number of different readers. It thus combines oral and written language in a dramatic way. In some versions of Readers Theatre, dramatised scenes complement the reading. Most texts are suitable for adaptation to Readers Theatre, for example factual texts, stories, poetry and biographies. The actual process of adapting a text to Readers Theatre is quite straightforward: it is simply a matter of dividing it up it into smaller units. In addition, some texts are already available in Readers Theatre form, especially those of Aaron Shepard in his books on Readers Theatre and on his Readers Theatre website (see Resources).

Different models of Readers' Theatre

There are two basic models of Readers Theatre: the ‘traditional model’ and the ‘developed model’. A Readers Theatre version of The fairy tale ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ is provided in this guide as an example of the traditional model of Readers' Theatre, including guidelines on how to use it.

The traditional model

The traditional model of Readers Theatre has a number of variants, but in principle the readers sit or stand in a row or a semi-circle. This model combines reading aloud with dramatisation, but makes a clear distinction between the two. Some pupils read aloud, while others dramatise scenes that complement the reading. The reading and dramatisation never take place at the same time.

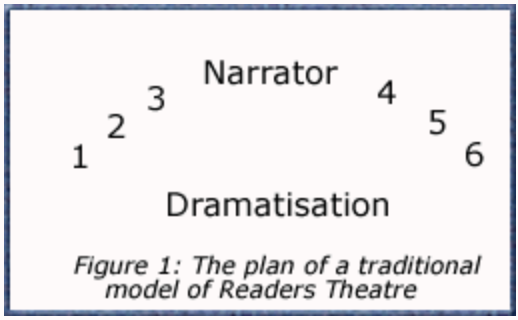

The traditional model variant presented here was introduced into Norway in 1984 by the late Professor Leighton Ballew, who was a guest of Sogn og Fjordane Teater at the time. I worked on a Readers Theatre project with him, which was a collaboration between the Theatre and local schools. In Ballew’s model seven readers sit in a semi-circle. One of the readers is called the ‘narrator’, and sits in the middle. The readers read very small units of a text, often a line or two, in a fixed order, until the whole text is completed. Figure 1 shows how the readers are organised in this model:

The reading always takes place in the following order: Narrator, 1, 6, 2, 5, 3, 4, Narrator, and so on. The Narrator always starts and finishes a reading sequence. Ballew stressed that Readers Theatre was an activity for all pupils, not just the best readers. The fact that very small units of text are read at a time make the reading manageable for pupils of all abilities.

An example

The following sequence illustrates the beginning of the Readers Theatre version of the fairy tale ‘Rumpelstiltskin’. The whole text is also provided in this guide as an example of a traditional Readers Theatre model. In ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ there are seven readers (including the narrator), and two to three pupils involved in the dramatised scenes.

Narrator: A long time ago, a miller lived with his daughter in a kingdom.

1 His daughter was very beautiful.

6 She was a kind, but shy girl.

2 The king was out riding one day and saw the miller’s daughter.

5 “What a beautiful girl!” he said.

3 “She’s more than beautiful” answered the miller. “She’s also clever. She can turn straw into gold!”

4 “That can’t be true?” said the king. “No one can turn straw into gold? Come to my castle tomorrow with your daughter. I want to see for myself.

Narrator: Well...OK,” said the miller. Now he was nervous.

The readers continue reading until a dramatised scene interrupts the reading. When that happens, the readers sit passively while other pupils dramatise in front of them. The first dramatised scene in this version is when the little man meets the miller’s daughter. There are two other dramatised scenes. When a dramatised scene is finished, the readers continue until another dramatised scene occurs. To make the reading more interesting and varied for the listeners, the readers sometimes stand before reading their lines. The biggest challenge for the readers, but something that makes the experience more powerful for the listeners, is if the readers look at whoever is reading a line at any given time. Doing that helps the listeners to focus on the different readers. The readers should not make any unnecessary movements while reading, for example touching their hair, as this may distract the listeners from the actual reading. Neither should they sit with legs crossed.

The developed model

In the developed model of Readers Theatre all participants ‘read’ parts of the text, but a distinction is made between ‘narrators’ and ‘characters’. There are no dramatised scenes, but readers who read the role of characters are free to move around the room, sit and stand and, for example, to use body language as they read. The same character is always read by the same reader. Those who are narrators usually place themselves in one fixed place in the room. For example, if there are four narrators, each one may place themselves in a corner of the room.

The beginning of the ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ text would look as follows if it were presented as a developed model of Readers Theatre. There would be four narrators and four characters: the miller, the king, the little man and the miller’s daughter.

Narrator 1: A long time ago, a miller lived with his daughter in a kingdom.

Narrator 2: His daughter was very beautiful.

Narrator 3: She was kind, but shy girl.

Narrator 4: The king was out riding one day and saw the miller’s daughter.

King: “What a beautiful girl!”

Miller: “She’s more than beautiful. She’s also clever. She can turn straw into gold!”

King: “That can’t be true! No one can turn straw into gold? Come to my castle tomorrow with your daughter. I want to see for myself.”

Miller: “Well...OK.”

Narrator 1: Now the miller was nervous, etc.

Teaching objectives

Readers Theatre incorporates a number of teaching objectives, which may be summed up as follows:

- Communicating a text orally in the form of group reading and dramatisation

- Promoting reading skills, for example pronunciation, stress and intonation

- Promoting reading fluency

- Increasing motivation and confidence in using English

- Promoting reading pleasure

- Acquiring the forms of language and vocabulary

Resources

Aaron Shephard has written three highly recommended books on ‘developed’ Readers Theatre, which are reasonable to buy and which include many Readers Theatre texts. The books are:

Readers on Stage (guidelines on Readers Theatre, with some example texts), Shepard Publications (ISBN: 978-0-938497-21-9)

Stories on Stage (A number of Readers Theatre stories), Shepard Publications (ISBN: 978-0938497-22-6)

Folktales on Stage (A number of Readers Theatre folktales), Shepard Publications (ISBN: 978-0-938497-20-2)

Aaron Shepard’s website (http://www.aaronshep.com/rt/index.html) contains a good deal of information about Readers Theatre, as well as a number of free texts that can be downloaded.

I wrote the following article on how Readers Theatre was used with a ‘fordypning’ group of pupils in lower secondary school:

Drew, I. 2009. Readers Theatre: How low achieving 9th graders experienced English lessons in a novel way. In Groven, B., Guldal, T.M, Lillemyr, O.F., Naastad, N. and Rønning, F. (eds), FoU i Praksis 2008, 51 – 58. Trondheim: Tapir akademisk forlag.

Other references

Pilarcik, M. 1986. Tools for the classroom. Creative writing as a group effort. Unterrichtspraxis, 19/2: 220-224

Preparations

The traditional model

The teacher adapts a text for Readers Theatre. The text is typed into a word document in small fragments, divided among the readers and the Narrator, as in the given example of ‘Rumpelstiltskin’. It is basically up to the teacher to decide how large the fragments are, but usually a fragment should be no more than two lines. The teacher also decides which scenes are to be dramatised and makes sure these are available separately for those involved in the dramatisation. Those involved in the dramatised scenes should also be given a copy of the reading part of the text, so that they know how their contribution fits in with the whole.

Assuming that the teacher has a text adaped for Readers Theatre, the following procedure should be followed. The assumption is that in a large class, different groups of pupils will be working with different Readers Theatre texts, both with respect to rehearsing them and presenting them to the rest of the class. The text of ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ will here be used to illustrate the preparations for using the traditional model of Readers Theatre, but the principles apply to any other text for which this model would be used.